New study: Immigrants little effect on jobs of US high school dropouts

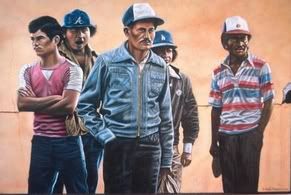

One of the most contentious arguments in the debate over the economic effects of immigration has been whether the influx new immigrants has had an adverse effect on the wages of native-born workers with the lowest levels of education. It has been widely accepted that for those native workers at the higher levels education and job skills, immigrants generally provide economic benefits, but the debate over how they effect those who labor at low-skill jobs or jobs requiring less educational attainment has fostered debate.

One of the most contentious arguments in the debate over the economic effects of immigration has been whether the influx new immigrants has had an adverse effect on the wages of native-born workers with the lowest levels of education. It has been widely accepted that for those native workers at the higher levels education and job skills, immigrants generally provide economic benefits, but the debate over how they effect those who labor at low-skill jobs or jobs requiring less educational attainment has fostered debate.

A new study from Giovanni Peri of the University of California, Davis and Chad Sparber of Colgate University has tackled this thorny issue and found that foreign and native-born workers with similarly low educational attainment in fact compliment each other in the workforce rather than compete.

This idea of "complimentary skills" is not a new one and has been examined not only by Professor Peri before, but numerous other economists. This study differs from those in that it contains forty years of data and looked at the actual tasks performed by each class of workers to see what jobs were being done by native-born workers as opposed to foreign born workers.

The study found that foreign born workers perform more manual and physical tasks, while native-born workers do tasks that are more language-intensive and interactive, and that native-born workers benefit from this specialization.

The study also examines the work of economist George Borjas that claimed that immigrant labor decreased the overall wages of less educated native workers by 8%. Peri and Sparber found that overall, the negative effects of foreign workers was only 0.7%.Documented and undocumented immigration has significantly affected US labor supply during the last few decades, though the economic effects of this immigration remain subject to debate. The most contentious issue is whether the particularly large inflow of immigrants with low levels of schooling has decreased the wage of native-born workers with similarly low educational attainment. If workers’ skills are differentiated only by their level of educational attainment, and workers of different skill levels are imperfectly substitutable, then a large flow of immigrants with limited schooling should reward more educated natives and hurt less educated ones.

This intuitive approach receives support in papers by George Borjas (2003, 2006) and George Borjas and Larry Katz (2005), which argue that immigration reduced real wages paid to native-born workers with no high school degree by four to five percent between 1980 and 2000. In contrast, Card (2001) and Lewis and Card (2005) employ city and state level data and find almost no effect of immigration on the relative wages of less educated workers. Moreover, their results are robust to the migration decisions of native-born workers, as they find that natives do not choose to move to areas with fewer immigrants. Thus, the relationship between immigration and wages appears to be more nuanced.

Ottaviano and Peri (2006) note that the effect of immigration depends crucially on the degree of substitution between native and foreign-born workers within each education group. That is, workers’ skills may be differentiated by more than traditional measurable characteristics such as educational attainment (and experience level). Native and foreign-born workers may have quite different skills, leading them to specialize in different productive tasks. For example, immigrants — particularly those with low levels of formal schooling — are likely to have inadequate language skills, imperfect knowledge of productive networks, and only limited awareness of social norms and intricacies of productive interactions. However, they have manual and physical skills similar to those of native-born workers. Therefore, foreign-born workers have a comparative advantage in occupations performing manual labor intensive tasks. On the other hand, native workers with little education will have a much better mastering of the language, local norms, rules, and networks. Thus, they have an advantage in performing interactive and coordination tasks. If less educated immigrants work in occupations that mostly perform manual tasks, natives move to occupations requiring more interactive tasks, and the two types of tasks are complements in production, then native workers can protect themselves against wage competition and benefit from immigration through specialization.

Though the assumptions in Ottaviano and Peri (2006) seem reasonable and are supported by anecdotal evidence, they require empirical verification. This paper employs US data for all 50 states (plus the District of Columbia) from 1960 to 2000 to determine whether task-specialization among native and foreign-born workers truly occurs.

…snip…

The data strongly support three key implications of our theory, which we formalize in a simple model in the first section of the paper. In states with large inflows of less educated immigrants: i) less educated native-born workers shifted their supply towards interactive tasks; ii) the total supply of manual relative to interactive skills increased at a faster rate than in states with low immigration and iii) the wage paid to manual relative to interactive tasks decreased. Less educated natives have responded to immigration by upgrading their occupations. That is, they leave manual task-intensive occupations for interaction-intensive ones. Given the positive wage effect of specializing in interactive skills, this shift augmented real wages paid to native-born workers.

..snip…

Finally, we use the structure of our model and our empirical results to calculate the effect of immigration and the related adjustment in task supply on average wages paid to native-born workers with a high school degree or less. Task complementarities and changes in native-born task supply together imply that the wage impact of immigration is quite small. These findings agree with those of Card (2001), Card and Lewis (2006), and Ottaviano and Peri (2006). At the same time they enrich the structural framework to analyze the effect of immigration first proposed by Borjas (2003) and then used in Borjas and Katz (2005), Ottaviano and Peri (2006), and Peri (2007).

…snip…

Our empirical analysis employed a dataset developed by Autor, Levy, and Murnane (2003) that measures the task-content of occupations in the United States between 1960 and 2000. We find strong evidence supporting three implications of our theoretical model:

i) On average, less educated immigrants supplied more manual relative to interactive tasks than natives

supplied. This tendency became stronger during the 1980s and 1990s.

ii) In states with large immigration among the less educated labor force, native workers shifted to occupations

intensive in interactive tasks, thereby reducing native workers’ relative supply of manual tasks. In states with

low immigration, native-born workers maintained a higher relative supply of manual tasks.

iii) In states with large immigration among the less educated labor force, there is a larger relative supply

of manual production tasks than in states with low levels of immigration. This implies that immigrants more

than compensate for the reduced manual skill supply among natives, and it ensures that manual task-intensive

occupations earn lower wages.

Since native-born workers respond to inflows of immigrant labor by specializing in interactive tasks, wage losses associated with immigration are minimal. Immigration caused wages paid to native-born workers with less than a high school degree to drop by just 0.7% between 1990 and 2000.

Comparative Advantages and Gains from Immigration Giovanni Peri (University of California, Davis and NBER), Chad Sparber (Colgate University) April, 2007

alternative link

One of the most heated debates over immigration and immigration reform has not been taking place in Congress or on the campaign trail. Over the last few years in the halls of academia a debate has raged between two opposing schools of labor economists trying to understand the ultimate costs and benefits of immigrant workers to the US economy. One camp claims that immigrants provided a net benefit to the economy and US workers, the other claims immigrants take jobs from US workers, particularly those with the least education and opportunities. Armed with statistical data, mathematical formulas, charts, and analytical theories, they have argued back and forth trying to answer a key question to any successful immigration policy: Are immigrant workers good or bad for the US economy and more importantly how do they effect the wages and job prospects for native-born workers?

One of the most heated debates over immigration and immigration reform has not been taking place in Congress or on the campaign trail. Over the last few years in the halls of academia a debate has raged between two opposing schools of labor economists trying to understand the ultimate costs and benefits of immigrant workers to the US economy. One camp claims that immigrants provided a net benefit to the economy and US workers, the other claims immigrants take jobs from US workers, particularly those with the least education and opportunities. Armed with statistical data, mathematical formulas, charts, and analytical theories, they have argued back and forth trying to answer a key question to any successful immigration policy: Are immigrant workers good or bad for the US economy and more importantly how do they effect the wages and job prospects for native-born workers?  To Borjas, a Cuban immigrant and the pre-eminent scholar in his field, the truth is pretty obvious: immigrants hurt the economic prospects of the Americans they compete with. And now that the biggest contingent of immigrants are poorly educated Mexicans, they hurt poorer Americans, especially African-Americans, the most.

To Borjas, a Cuban immigrant and the pre-eminent scholar in his field, the truth is pretty obvious: immigrants hurt the economic prospects of the Americans they compete with. And now that the biggest contingent of immigrants are poorly educated Mexicans, they hurt poorer Americans, especially African-Americans, the most.