Border fence boondoggle, it's more than just the cost

One of the top stories of the day comes from a recently released report from the Congressional Research Service that shows the "cost of building and maintaining a double set of steel fences along 700 miles of the U.S.-Mexico border could be five to 25 times greater than congressional leaders forecast last year, or as much as $49 billion over the expected 25-year life span."

Proponents of the border security measure were quick to make the rounds of the usual cable outlets to dispute the studies findings. Tom Tancredo (R-CO), a leading advocate for the border wall, questioned the studies assertions, and brought up the success of the existing wall in San Diego to make his case. Admitting having not actually seen the study prepared by CRS, the agency responsible for public policy research for Congress, Tancredo claimed that something was "very peculiar" about the study.

Had Tom taken the time to read through the 45 page analysis, he would have seen that the costs of the fence may be the least of the problems.

tags: immigration, border fence , CRS, border security

Anti-immigration advocates like Tom Tancredo (R-CO), or Duncan Hunter (R-CA) love to point to the success of the 14 mile border wall in San Diego as their model for effective border security. In his interview on MSNB, Tancredo was quick to point out that the wall had only cost $1million a mile to build and the new report's cost estimates were "very peculiar". Hunter remarked about the dramatic changes the wall had made in the San Diego area in regards to the flow of undocumented migrants. What none of the immigration hawks mentioned was the fact that the original 14 mile wall did absolutely nothing, and that it took millions of dollars of additional resources and manpower to make it even reasonably effective.

Tancredo's $1 million dollar a mile wall…well not really

…in 1990 the USBP began erecting a physical barrier to deter illegal entries and drug smuggling. The ensuing “primary” fence covered the first 14 miles of the border, starting from the Pacific Ocean, and was constructed of 10-foot-high welded steel.

The primary fence, by itself, did not have a discernible impact on the influx of unauthorized aliens coming across the border in San Diego. As a result of this, Operation Gatekeeper was officially announced in the San Diego sector on October 1, 1994. The chief elements of the operation were large increases in the overall manpower of the sector, and the deployment of USBP personnel directly along the border to deter illegal entry.

The strategic plan called for three tiers of agent deployment. The first tier of agents was deployed to fixed positions on the border. The agents in this first tier were charged with preventing illegal entry, apprehending those who attempted to enter, and generally observing the border. A second tier of agents was deployed north of the border in the corridors that were heavily used by illegal aliens… The third tier of agents were typically assigned to man vehicle checkpoints further inland to apprehend the traffic that eluded the first two tiers.

Operation Gatekeeper resulted in significant increases in the manpower and other resources deployed to San Diego sector. Agents received additional night vision goggles, portable radios, and four-wheel drive vehicles, and light towers and seismic sensors were deployed. According to the former INS, between October 1994 and June of 1998, San Diego sector saw the following increases in resources:

Border Security: Barriers along the U.S. International Border Congressional Research Service, Updated December 12, 2006, pg 3

Even with these increased resources, the fence still did not perform up to par. The primary fence in combination with the increased manpower did cut down on immigrant incursions in the region but proved to be both fiscally and environmentally costly. A 1993 INS study recommended a three-tiered fence system with roads between

In 1996, construction began on the secondary fence that had been recommended by the Sandia(INS) study with congressional approval. The new fence was to parallel the fourteen miles of primary fence already constructed on land patrolled by the Imperial Beach Station of the San Diego sector, and included permanent lighting as well as an access road in between the two layers of fencing. Of the 14 miles of fencing authorized to be constructed by IIRIRA, nine miles of the triple fence had been completed by the end of FY2005. Two sections, including the final three mile stretch of fence that leads to the Pacific Ocean, have not been finished.

Border Security: Barriers along the U.S. International Border Congressional Research Service, Updated December 12, 2006, pg 6

As to the final cost of construction for Rep. Tancredo's "$1million a mile San Diego fence system", the DHS is currently estimating that it will cost an additional $66 million to finish the San Diego fence, bringing overall costs for this 14 mile-long project to $127 million. These numbers do not include the funding for the increased manpower and resources or the maintenance on the fence system which the Army Corp of Engineers puts as high as $7500 a year per mile.

Additionally, the Corps of Engineers study notes that the Sandia fence would possibly need to be replaced in the fifth year of operation and in every fourth year thereafter if man-made damage to the fence was “severe and ongoing.” For this reason, in the study the Corps of Engineers noted that the net present value of the fence after 25 years of operation, per mile, would range from $11.1 million to $61.6 million.

Border Security: Barriers along the U.S. International Border Congressional Research Service, Updated December 12, 2006, pg 21

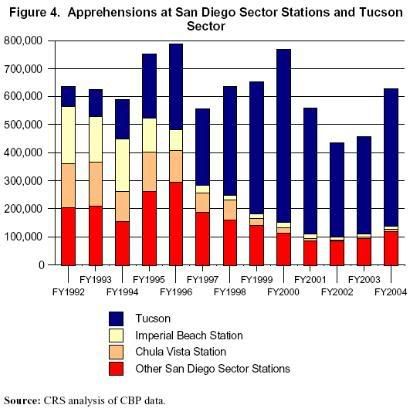

If you can't go over the wall…go around it

While the San Diego fence, combined with an increase in agents and other resources in the USBP’s San Diego sector, has proven effective in reducing the number of apprehensions made in that sector, there is considerable evidence that the flow of illegal immigration has adapted to this enforcement posture and has shifted to the more remote areas of the Arizona desert. Nationally, the USBP made 1.2 million apprehensions in 1992 and again in 2004, suggesting that the increased enforcement in San Diego sector has had little impact on overall apprehensions.

Border Security: Barriers along the U.S. International Border Congressional Research Service, Updated December 12, 2006, pg 1 Statistics show that the strategy of concentrating agents, resources and barriers in urban areas that traditionally had high levels of immigrant incursion such as San Diego or El Paso has only moved the flow of migration to more remote and dangerous areas.

Statistics show that the strategy of concentrating agents, resources and barriers in urban areas that traditionally had high levels of immigrant incursion such as San Diego or El Paso has only moved the flow of migration to more remote and dangerous areas.

Since the mid-nineties the Tuscon Sector, responsible for the Arizona border, has seen an exponential growth in migrant crossings. This shift in migration patterns has had the unintended consequence of an increase in the numbers of migrant deaths per year. In the early nineties on average 200 migrants died each year trying to cross the desert. By 2005 that number more than doubled to 472.

Additionally, this shift in migration patterns has put added pressure on rural areas, both economically and environmentally. Unfortunately, this shift has also brought with it a relative increase in crime to areas least able to address the problem. Along with economic migrants looking for a better life, drug smugglers and other criminals have been driven to the desert as their new point of entry.

Another unintended consequence of this enforcement posture may have been a relative increase, compared to the national average, in crime along the border in these more remote regions. While crime rates in San Diego, CA and El Paso, TX, have declined over the past 15 years, the reduction in crime rates along the more rural areas of the border have lagged behind the national trends

Border Security: Barriers along the U.S. International Border Congressional Research Service, Updated December 12, 2006, pg 32

If you can't go over the wall…go under it

While most have chosen to go around the walls, some have chosen to tunnel their way under them. As of January 2006, twenty-one tunnels had been discovered since 9/11. One in San Diego, under Tom Tancredo's flagship wall, was over 2,400 feet long with reinforced concrete walls and interior lighting.

Yet, these smuggling tunnels represent only the tip of the iceberg in the world of subterranean international travel. In many border towns and cities the existing infrastructure of sewers, storm drains, and utility tunnels provide an easy path for those willing to brave the underground world.

One mile deep into the drafty tunnel under this hilly frontier city, a flashlight beam cuts through the pitch-black darkness and illuminates a yellow line painted on the concrete wall: the U.S.-Mexico border.

…

Inside the largest known tunnels on the border — two passages that make up an enormous drainage system linking Nogales, Mexico, with Nogales, Ariz. — migrants stumble blindly through toxic puddles and duck low-flying bats. Methamphetamine-addicted assailants lurk. And young men working as drug mules lug burlap sacks filled with contraband.

…

llegal immigrants have breached drainage systems all the way along the border, from El Paso to San Diego. Most of them are of the claustrophobic crawl-through variety that prevents large-scale incursions.

The Nogales tunnels, by comparison, are superhighways.

Once open waterways, today they stretch for miles under the traffic-clogged downtown streets of both cities, zigzagging roughly parallel to each other.

In the smaller one, called the Morley Tunnel, an ankle-high stream of raw sewage and chemical runoff from factories in Mexico usually flows. The neighboring Grand Tunnel is up to 15 feet high and wide enough to fit a Humvee. Dozens of illegal immigrants can travel through it at one time.

Above ground, fences, sensors and stadium lighting clearly separate the two cities. Underground, they remain linked of necessity by the system built decades ago to channel monsoon rains.

LA Times

Across the length of the border existing infrastructure provides a ready path of entry those willing to brave them.

And so, welcome to the brave new world of cross-border tunnel migration and militarization – and, what could be the glimpse of a future (sub)urban world as more nation states wall off their borders from the increasing flows of global migration.

Essentially, the infrastructure has been left an exhausted corpse of overgrown concrete appendages and flogged lungs that today becomes a kind of mysteriously populated anti-city lurking below the real city above. It’s partly a thriving subterranean landscape with thousands of people traversing and living and conducting their own brand of commerce, but it’s also partly a massive industrial grave stewing with noxious hazards and quiet anonymous deaths.

"Orwellian Wormholes" Subtopia

Walls don't always keep you out …sometimes they keep you in

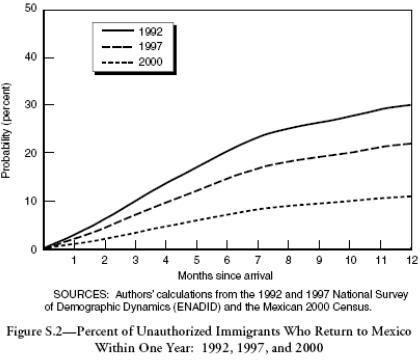

One of the biggest unintended consequences of increased border security has been its effect on preventing undocumented migrants from leaving the country to return back to their homes in their countries of origin. At a recent immigration symposium at the University of Chicago, Belinda Reyes, an assistant professor in the College of Ethnic Studies at San Francisco State, presented a regression analysis suggesting that the more impregnable the barrier, the more unauthorized migrants wind up living in the United States. This presentation was an update to Reyes 2002 study "Holding the Line? The Effect of the Recent Border Build-up on Unauthorized Immigration" that found that with increased security between 1992 and 2000, the number of Mexican migrants returning home each year went down from 20% to 7%. It is only safe to assume that those numbers have decreased dramatically in the last six years.

There is strong evidence that unauthorized migrants are staying longer in the United States during the period of increased enforcement.

The findings based on both the national data and the Mexican Migration Project (MMP)5 sample indicate a decline in the probability of return in the 1990s. Analysis of the MMP sample shows no statistically significant

effect of the build-up on the probability of return. But the national data indicate a continuing decline in the probability of return in the latter part of the 1990s, which could be the result of an increase in border enforcement (see Figure S.2).

Data from a 1992 survey in Mexico indicate that 20 percent of the people who moved to the United States 24 months prior to the survey year returned to Mexico within six months of migration. By 1997, this portion had declined to 15 percent. By the time of the Mexican 2000 Census, only 7 percent of those who moved 24 months prior to the census returned to Mexico within the first six months and only 11 percent had returned within a year.

link "Holding the Line? The Effect of the Recent Border Build-up on Unauthorized Immigration", Belinda I. Reyes, Hans P. Johnson, Richard Van Swearingen, Public Policy Institute of California, 2002

conclusions

If Rep. Tancredo and his friends in the border security camp took the time to actually read some of the research provided for them at taxpayer's expense, they would see that their insistence on more fences and walls clearly provides neither security nor an effective means to curb undocumented migration. The walls are overly costly and are ineffective without huge amounts of added manpower and resources. The existing infrastructure in many areas makes them ineffective. Environmentally they are a disaster and have far too many unintended negative effects. Thus far they have only shifted the patterns of migration, bringing added death and crime to more rural areas and have kept immigrants from naturally returning home.

Perhaps it's possible that the Congressional Research Service, Army Corp of Engineers, Customs and Border Protection, Department of Homeland Security, and the Congressional Budget Office are all wrong and the San Diego border fence has been a great success as Rep. Tancredo claims….but then again …maybe not.

A possible issue for Congress to consider as it debates expanding the existing border fencing concerns what the unintended consequences of this expansion could be. Given the re-routing of migration flows that have already occurred, are DHS and the relevant border communities prepared to handle the increased flow of illegal

migration to non-reinforced areas? Is DHS prepared to deal with an increase in the phenomenon of cross-border tunnels and other attempts to defeat the purpose of the fencing? What will the impact on crime rates be along the unreinforced areas of the border? Will USBP agents be required to spend some of their patrolling time

guarding the fence?

Border Security: Barriers along the U.S. International Border Congressional Research Service, Updated December 12, 2006, pg 33

No comments:

Post a Comment